The Artillery Driver

Part One, History

By: Dave Fox, Driver Ferguson's Battery

Note: This article first appeared in the Camp Chase Gazette, March of 1997.

![]()

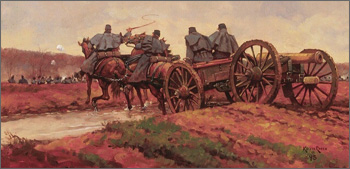

"Artillery Forward" by Keith Rocco

I take pen in hand in some discomfort, the warm afterglow of a recent fall from a horse which gained me bruises the color of autumn leaves, pulled muscles, an equine version of whiplash and a couple of cracked ribs which make coughing a spiritual experience. All this from a tumble from a perfectly good little mount out for a genteel trot in a pasture. As I lay kissing the turf, I was minded of my chosen Reenactors persona, an artillery driver with Ferguson's Battery Army of Tennessee.

For a driver to have been thrown from a plunging near leader even in drill would likely have resulted in his being battered by a drum roll of the iron shod hooves of several half-ton dray horses; perhaps lead, swing and wheel, both near and off. In the unlikely event he survived being dragged amid those twenty-four hooves by traces and tumbled free, he still faced being rolled like a pill bug under the axles of the limber, gun or caisson, splintering one's spine and long bones while an iron tired wheel or two crushed pelvis or chest leaving a pulped wreak. This horror was likely observed during the Civil War by Union General Lew Wallace who may have used it to pattern his vivid description of the chariot-trampled Messula in his famous post-war novel Ben Hur.

Artillery drivers, then termed postillions, materialized soon after wheels were levered under the early hooped gun tubes. In the Middle Ages, postillions were simple civilian husbandmen who hired themselves and offered their own oxen or horses out to professional gunners who, in turn, hired themselves and perhaps their privately owned field guns to a king, lord or cause on contract for a given campaign. Upon the early adoption of the wheeled limber, postillions rode their draft horses to lend direction and control, hauling the guns, caisson wagons, and general supply transport.

Mercenary gunners were held in superstitious awe, members of something of a guild or union, and were, with their guns, so valuable that even after a catastrophic defeat the victors would likely protect them as useful turncoats. Not so the postillions, a country bumpkin who received no respect from his betters and whose stock was liable to confiscation over his dead body. In return, no one anticipates civilian postillions to risk themselves or their valuable animals in actual battle. Thus they unhitched well out of danger, requiring each cumbersome gun to be manhandled into action by large squads of pioneers and matrosses, placing acute restrictions on field artillery's tactical usefulness.

Amazingly, this system persisted for centuries, in spite of the military regularizing of the gunner and crew: professional artillerists depend upon civilian contract postillions who would stay well clear of harm's way and who were not subject to military discipline. This limited artillery maneuver on the field of action to the abilities of matrosses harnessed to the pieces by pull ropes called bricoles and leading to development of cannon little larger than oversized muskets on wheels to create mobility. The archaic system cried for reform, which began in the decades surrounding the turn of the 19th century when postillions began to be styled "drivers".

First, the drivers and dray animals were made part of the regular military establishment and subjected to regular military discipline. A corps of soldier-drivers opened up vistas of massing guns during battle and the Napoleon tactic of galloping light batteries right up to white-of-their-eyes ranges, unlimbering, and blasting slow-moving infantry masses with up to 15 rounds of grape per minute per gun. Napoleon, you'll recall, was a trained artilleryman. From being merely the thunderous opener of combat, too cumbersome to follow the action, the field artillery became a glamorous if dangerous arbiter of the field, the King of Battle, partially because of a change in the role of drivers.

Second,

soldier-drivers ceased to form their own separate organization and were assigned

to individual artillery companies and, finally, by the Mexican War they

crossed-trained as cannoneers so as to be available to man the guns in case of

emergency. It is unlikely this later use of drivers was often made in practice:

if gun crews were being decimated, and likewise decimated the drivers, the

guns would be immobilized and rendered useless and subject to capture. At

When

Lee's field batteries bogged down into siege warfare in 1864 and the guns were

immobilized in the

As

I sit here nursing my many aches, I also recall finding piles of rotting

artillery harness in an old equipment dump in the hills at Fort Sill in 1967. My

first sergeant was a grizzled old horse artillerymen and the year I was born the

last drivers, heirs to a proud tradition, were whipping their lead, swing, or

wheel horses and bouncing their limbered 75's around the same fields I later

trained on. We'll never see their like again.

Next: the driver persona in reenacting

|

|